A lot of people complain that college isn’t doing a good job preparing people for the workforce.

They toss around statistics like “only 27% of college grads have jobs related to their majors” and “only 62% of college grads have a job that requires a college degree”. Evidently, the only goal of college nowadays is career preparation, and colleges (or maybe college graduates) are failing at this goal.

Why is that? What’s wrong?

To answer that, let’s check out the history of college.

We’ll go back 200 years, to the Revolutionary War. When the first publicly-funded colleges came into existence, their purpose was to educate the top 5-10% of highly gifted white boys, so that they could become leaders and exceptional men. Our modern sensibilities might be offended by the exclusiveness of “small percentage of highly gifted white boys”—it leaves out girls, people of color, and non-highly-gifted white boys—but for the time, it was very progressive. In Britain, college was explicitly a privilege for only the very wealthy. The Americans, then, wanted to move away from that; they decided that college should be available to any highly gifted white boy, regardless of income.

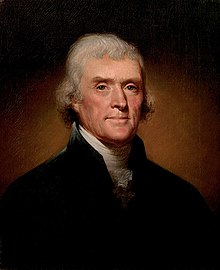

One of the main contributors to this ideal was Thomas Jefferson, who wrote Bill 79, “A Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge”, which was presented numerous times through the 1770s and 80s before a heavily revised version was put into law in 1796.

One of the main contributors to this ideal was Thomas Jefferson, who wrote Bill 79, “A Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge”, which was presented numerous times through the 1770s and 80s before a heavily revised version was put into law in 1796.

This was still the general attitude through the 1800s. When W.E.B. Du Bois argued for the education of African Americans, he expressly said that college is for only the “talented tenth”, or the “best minds of the race”, so that they can “reach their potential and become leaders”.

“The Negro race, like all races, is going to be saved by its exceptional men. The problem of education, then among Negroes must first of all deal with the Talented Tenth; it is the problem of developing the best of this race that they may guide the mass away from the contamination and death of the worst, in their own and other races.”

This view remained until the turn of the twentieth century, when it gradually started to change.

College became a status symbol: after all, it was only available to the top 5-10% of people, so having gotten into college meant you had something special. Something special that employers wanted working for them. College graduates, then, got their pick of the best jobs.

Since everyone wants great jobs, everyone wanted college. As such, the GI Bill was passed, opening college to a much larger population following WW2. The problem was that college itself was not causing people to get great jobs, it was a status symbol that was merely correlated with getting great jobs, and people committed the fallacy of post hoc ergo propter hoc.

As college became available to more and more people, it became less useful as a symbol.

The symbol was, after all, about being part of an elite few. When this happened, college stopped guaranteeing good jobs, or in fact any jobs at all. But yet, the cultural zeitgeist had shifted: college was for jobs now, not for educating future leaders. It doesn’t matter that the curriculum has hardly changed at all since 1851. College is supposed to magically procure jobs, despite the fact that it has absolutely no way to do that.

College had never been designed to prepare people for specific careers that required specific skills. For the elite future leaders it was designed for, it taught more generic things like developing a cultured and educated and intellectual character. This is great and all, but it doesn’t give you diddly for actual marketable skills.

College had never been designed to prepare people for specific careers that required specific skills. For the elite future leaders it was designed for, it taught more generic things like developing a cultured and educated and intellectual character. This is great and all, but it doesn’t give you diddly for actual marketable skills.

During the actual time period, when the top 5% were going to college to learn how to be great leaders or whatever, everyone else was learning actual job skills through trade apprenticeships. In fact, many of the leaders did this too: they both went to college and apprenticed at a trade, so they could have a means of making a living while they worked on shaping the nation. Being a person who shapes a nation doesn’t come with a paycheck.

So, why is college failing at getting people jobs?

It wasn’t designed to do that in the first place. During the brief period that it did do that, it was because of correlation based on rarity and status, not causation based on education. And now, despite being basically the same thing that it’s always been, college is saddled with the artificial purpose of getting jobs for graduates, which it is incapable of doing.

Once you know the real history, all the artificial, retroactive explanations of the modern day fall away. All the justifications of the continued existence and high price of college fail to make sense. You start to notice that there is literally nothing that colleges do or pretend to do that can’t be done more effectively somewhere else for a tiny fraction of the cost.

You want a liberal arts education?

Sure! Go to the library. Read the classics. Read Shakespeare and Dante and then learn Latin and read Caesar and Catullus and Cicero. Go to museums and learn about art. Go to symphonies and learn about music. You don’t need a university for a liberal arts education.

You want to learn more pragmatic stuff, like math and coding and writing?

Sure! Take some online courses. I recommend Gotham Writers, Udemy, Free Code Camp, Edhesive, and Khan Academy.

You want a great career?

Sure! Look over the job market, see what kinds of skills are marketable, see what kinds of skills you’ve got, and start looking. If you’re just getting started, I recommend the Praxis program.

You want to network with other smart, interesting, accomplished people?

Sure! There are a huge number of online groups and forums, as well as tons of conventions and other in-person gatherings. Here’s a guide on how to build your network without college.

You want a status symbol to put on your resume?

Well, okay, maybe for that you want college. Get good grades in high school, get 5s on APs, ace the hell out of the SAT, get National Merit, don’t forget your extracurriculars… basically work your butt off for four years in high school, then apply to a bunch of colleges. If you’re both lucky and successful, you’ll get the opportunity to pay a bunch of money in order to work your butt off for four more years so you can put Harvard, Stanford, Yale, or whatever on your resume. And yes, this is a very useful and valuable status symbol. But it’s taken eight years of your life and possibly hundreds of thousands of dollars.

In case you want a different route than that, try this:

Go apply for a job at prestigious companies in your chosen field, and if you don’t get in, develop your resume and skillsets until you do. It’ll require about as much hard work as college, but unlike college, you’ll actually learn useful skills in the process. Also unlike college, you won’t be in debt by the end; rather, you’ll have been paid for your trouble.

The only reason you should consider going to college is if you’re planning on going into a field that is very, very strict about requiring one. (“All the job listings say they require one” does not count.) For example, if you want to be an accountant, you need a CPA. You cannot sit the CPA exam without 150 credit hours of college, so you’re kinda stuck there. Similar concept with doctors, lawyers, and the like.

Still, in those circumstances, it’s just because the world hasn’t caught up to the uselessness of college yet.

So, should you go to college? Maybe. It depends on your specific goals. But is college the right path for everyone? Absolutely not. And is it a surprise that college isn’t doing a good job at preparing people for careers, given the history? Absolutely not. Actually, it’s a surprise that it’s doing as well as it is.

For everyone to have a good path, the entire educational system needs to be overhauled.

But for any given individual, just think long and hard about your career. Don’t march in lockstep down the college path just because college.

Jenya is a current Praxis participant working towards getting an internship in software development and technology. After a college prep intensive homeschooled high school including five APs, she became a four-year college opt-out. See more of her posts at jenyalestina.com/blog.

Jenya is a current Praxis participant working towards getting an internship in software development and technology. After a college prep intensive homeschooled high school including five APs, she became a four-year college opt-out. See more of her posts at jenyalestina.com/blog.

November 5, 2018